My mother is from a Spanish village nestled in the Sierra mountain range of the Sierra Del Segura in the central southern region of Castilla La Mancha, and the province of Albacete. She migrated to the United States in the 1960s. From as far back as I can remember, she and I would make the long journey from South Carolina to Peñarrubia, the name of the village, to spend summers at what then seemed like another planet. I can remember no running hot water or air conditioning, and the television had only one station that played 2 hours a day. My grandfather would even ride me on his donkey to tend to his fields by the river, on the same trail my cousins and I would take on a hot summer day for a cold swim. My shoes would stain red from the intense color of the earth.

Peñarrubia means Blonde Rock, and it is named after this gigantic rock that sits high and majestic over the village, shading its agricultural valley of olive and almond trees. At the very top, we know that once upon a time there was an Iberian settlement (6th century BC to most likely the 2nd) that made pottery of mostly vessels for holding water and storing food, plates and, bowls. Little ceramic pieces can still be found scattered and embedded underneath the prickly arid terrain of wild thyme, sage, and rosemary in between mostly bare boulders and small pines. The mountain goats and wild boar roam freely with a random visitor or trail runner from time to time that climbs to the top to take a selfie by the old telephone tower looking down over the breath taking view.

A few years ago, now living in Madrid, recently married, and a country home built in Peñarrubia I decided to take up ceramics at a local neighborhood cultural center. I have a B.F.A. and have been a commercial and artistic photographer for many years now, so it was not far from my reach. In class one day, it suddenly occurred to me that the clay my ancestors used back in Peñarrubia must have come from near the river “Segura”, and must be the same clay that stained my shoes red as a little girl. I also later came to find out that within the last century, this village produced roof tiles and that a grouping of houses here is called “La Teja” meaning the tile, nicknamed rightly so. That is when I began to make my own clay, first by firing in an electric kiln in order to make samples and to make sure it was workable.

In March 2020 I was on a photographic assignment in Costa Rica when the news of people contracting something called the Corona was happening in Italy. It became an immediate reality of urgency to get back home to Madrid as soon as possible. Ironically, the day before on my travels I visited a community of Chorotega Indian potters and gathered even more hands-on information on how people throughout the centuries in Central America have used traditional techniques passed down from generations to make earthen pottery from local wild clay and fired in traditional wood-burning kilns.

Upon my return, my husband, son and I packed up the car with as much food as possible and headed to our country house in Peñarrubia 4 days before the state of alarm and the national quarantine hit Spain on March 12th. That weekend would be the last time I would head down to the river or even leave the compound of my house for the next couple of months. Thank goodness I had filled up buckets with tons of clay earth, and ordered a hand wheel from Amazon just in time.

As I look back, the national Covid quarantine was my opportunity for my first conceptual ceramics project, since I did not have an electrical kiln I decided to try a pit fire.

My house is filled with books of art, which became of great use. I focused on the history of people making not only useful ceramic objects, but also ones that had symbolic cultural references. The essential basic elements found in nature are brought together in this discipline and have secretly told us stories about humanity for many years spanning different eras and cultures. This is so primitive I thought, and at the same time quite complex. The fear of the end of the world as we knew it during those first few weeks of lockdown made me think as long as I make use out of all these natural resources I am surrounded by and create relevant objects of art I can also interpret what is happening today and somehow get through this in sound mind and body.

As soon as the clay was ready, which took a few weeks; I set up my studio in the kitchen and surrounded myself with what would be my new world. Everything I needed was there except for the fire.

The sensation of wet clay in between my fingers brought me back to those simple and strong feelings of my childhood. When bored as an only child I would lock myself in the bathroom and make soups out of everything in the cabinets, mixing shampoo, creams, and toothpaste, playing, and getting pleasure from the goo and mess that had been made. Clay also has that infantile and primitive aspect in itself. It is used in most preschools and kindergartens because of the capability of fostering eye and hand coordination, response to emotional expression, and a great way of extending one´s attention span. Women have tended to the kitchen in most societies and not only fed their children, and families but got great pleasure in creating edible recipes. Being in the kitchen and making ceramics also brought me closer to my mother in a way, she was stuck in the USA, and to the happiness, I felt as a child.

I started with making coiled cups and getting familiar with building basic forms by looking at Japanese ceramics and even Greek and African. It became a ritualistic therapy, creeping out of bed early in the morning to get to “work” before any interruptions were possible. Every day I sculpted until I thought the pieces were ready for firing, which needless to say would be my biggest challenge. The Internet and videos played on my iPhone and computer during the drying times. Would it be a pit fire, a sagger fire, or a brick oven? I decided on a pit fire. The next step was hunting and gathering. Until approximately 12,000 years ago, all humans practiced hunting and gathering, this lifestyle was nomadic, and their mobility was a survival strategy. We started saving all the fruit peelings we were eating, especially bananas and oranges; saved nutshells, gathered leaves and sticks from the garden, pine cones, straw, I even found copper fungicide in the storage room, steel wool, salt, and sugar. When we were allowed into town for grocery shopping, I called a friend who had horses and, he gave me a sack of manure, and another carpenter friend a sack of wood shavings.

A few miles down the road from Peñarrubia is a reservoir. A bad streak of summer forest fires had left behind petrified wood that had been washing up over the winter onto its shores. I made various early morning scavenger trips, picking up as much wood as I could.

In the backyard, there was a grown-over vegetable garden that the rainy spring had moistened just enough making it easy to pull up the weeds and dig a proper hole for the decided pit fire.

The pit fire was the most sacred and mysterious of firing choices, and considering the circumstances it was the most natural one as well. My gathered materials were by then placed in piles and all the fireplace utensils of shovels, rakes and such I could find organized nearby. The weather channel was frequented because if there were rain and wind it obviously would not be the best of conditions for a fire. It happened to be a full moon right when all my stars lined up, and early that next afternoon I dressed into old clothes in order to build the desired pit up with wood in the shape of a beehive.

I baked the clay pieces first in the kitchen oven at 190 degrees for 3 hours, this would ensure the best survival rate possible, as I was sure that at least half would be lost to breakage by combustion from the heating process and my lack of experience.

The hive was lined with old bricks lying in the bottom of the hole and then layered with a bed of wood shavings and horse manure so that when the pieces were placed in they would be comfortable from the weight of all the other materials that would later be placed on top of them, this would also stain them black and gray from the smothering of the smoke twirling underneath. Straw weaved in and out as well so that salt and other minerals could be sprinkled within. We had old pallets of wood lying, around along with old magazine pages and then tinder. A can of gasoline from the lawnmower came in handy, so some of that was sprayed before the match was thrown in. Flames went up in smoke and my N95 mask found another reason to stay on my face without a doubt.

The fire swirled and spewed up traveling hot air in a spectacular motion, creating a story from within that would later emerge from the ashes. The temperature quickly rose and so far I did not hear any pops, which was a good sign.

For the next 3 hours to maintain this energy I fed the fire with driftwood, pine, old and dried up rosemary and thyme plants, a landscape of coals started to blanket the near ceramic pieces that sporadically surfaced for air. I could see parts of them from time to time and how they were changing colors, bright transparent red to almost blue, inside the coals were making the magic of now a dwindling bonfire. It was time to cover it all up and walk away for the next day or two. My stepfather had made a metal panel with a frame and a grate of iron rods for roasting a pig one Christmas, which came in handy to lie on top.

Hours later before getting into bed, I could not help but lift off the top and took a quick peek, (something quite dangerous to do because the cold air can crack the pieces) it was beautiful. A dance was happening. The only light anywhere around was the red-hot coals and glowing embers exhibiting their frolic as they flickered and moved to shift sparks like waves when hit by the nightlight of the moon; red diamonds sparkling harmonious sizzles whispering secrets as I crouched over the hole of what was once the fire. What a beautiful site that night, of course, I was filled with adrenaline.

I could hardly sleep thinking about what was going on out there. Which pieces might be broken and which others would survive; their tones, colors, and markings? All of this would be the result of basic instincts, primitive fire, earth, water, chemistry, and some science mixed together. At sunrise, I couldn´t take it anymore so in my pajamas I walked through the wet dewy grass and sat on the edge of the old garden and slowly lifted off the metal top. There was still some carbonized matter fueling around amongst the ash, but mostly the fire had burned out completely. Wearing thick garden gloves, I pulled them out one by one and sat them on the earth and stared in total amazement. I should have waited another day, which would have avoided a few new cracks that happened.

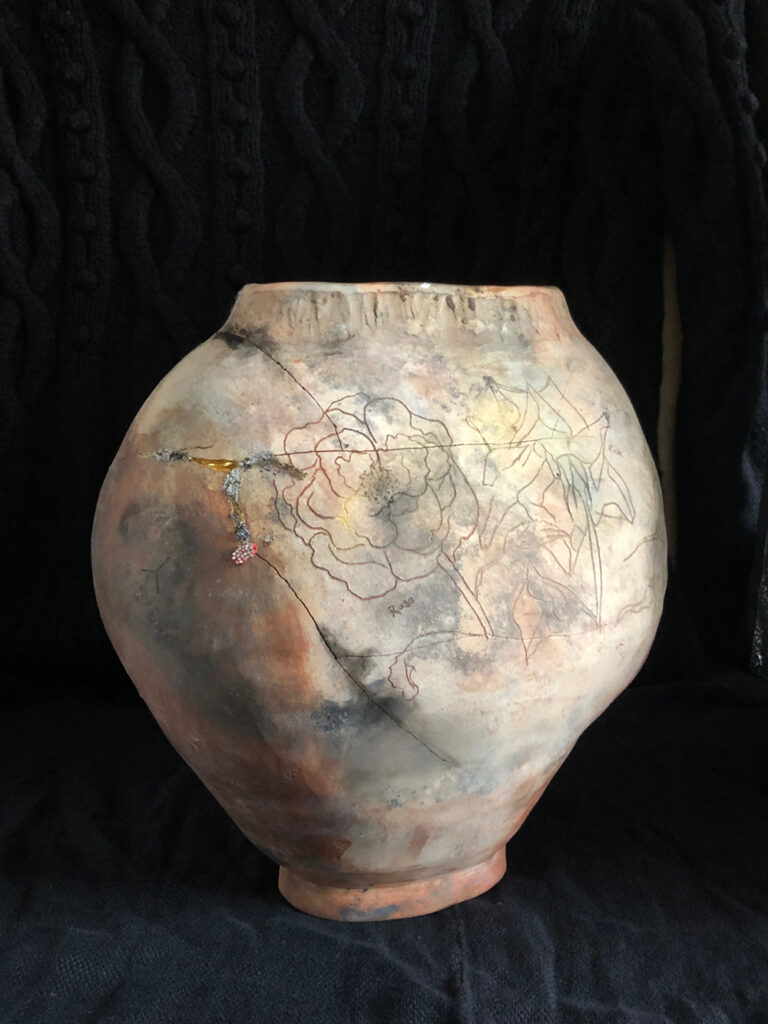

They definitely had stories written on each surface. The emotion, conversations, and thoughts that passed over each creation shaped them with individual characteristics. The cooling down solidified their pores and embraced their surfaces with textures of shaded tones, mostly black, gray, copper, and tan. The only piece that broke was the one I wrapped in aluminum foil and poured half a bag of salt onto, it basically corroded. This was my first fire! The second and third would be different.

During the second fire, I let in more air. I laid the metal top on overnight just like the time before but gave the pieces more room to breathe by not lying as much straw and sawdust down, this would let up on the black from smothered smoke and gave them a chance for a more overall smoky gray color with some greenish tones as I threw in cut grass just when they hit what I thought was the hottest point. Learning from my mistakes, I left out the salt. I had more breakage this time, especially a big vase I spent a good 10 days on. This I learned was from the extreme change in temperatures and too much air, I basically went too fast. It takes patience.

The third fire was also different. I only used driftwood this time, some salt around the bedding but not on the pieces, and not much fruit peelings, loosely used manure and straw letting the air once again circulate. These pieces came out with tones of, peach, yellow, green, gray, black, and even copper.

Unfortunately, most everything broke in this fire. I also found out that materials like salt must be added at the hottest moment otherwise it doesn´t make an effect, aka Raku.

Our stay during the Covid pandemic was coming to an end, time flew by at such an alarming rate that I didn´t even scratch the surface of all the things I had on my list to do, although what I did accomplish was my first ceramic prototypes and what would be my style of ceramics for years to come.

I now am working on an even bigger project that all began here. My artistic work has taken a turn and has more meaning; it was the purpose I had long been searching for. The activity of the fire and how it can change the earth is perplexing and profound. Fire has changed the way humans live and in part is the element that has driven evolution to where we are today, where would we be

Photos by Ana Nance.

Now located in Madrid, Spain.

My Career has been in photography for over 30 years. I graduating with a Fine Arts Degree in 1991 from Savannah College of Art and Design and moved to New York City where I was based as an artist and editorial photographer. Then in 2001 I relocated to Madrid, Spain, born to a Spanish mother it was a natural choice.

Most recently I have incorporated ceramics into my dialogue along with the research of new techniques brought out from the past in order to preserve and learn from our past as I dive into the future, also incorporating photography, and more to come.

Ana Nance’s Info:

Instagram: @anananceceramics