In 2008 I quit my university teaching job, gave away all my possessions, and bought a one way plane ticket to Tokyo. With no personal connections, no language skills, and very limited financial resources, I set out determined to change my life and become a working studio potter in Japan. Following over a decade of intense labor and experimentation, I now hunt and research wild clays and fire a self built anagama kiln in the isolated mountainous outskirts of Kyoto. Through the laborious task of wood firing pottery I seek purity within myself, an attempt at edification.

This summer I celebrate ten years of exhibiting at Gallery Utsuwakan. Rising to popularity in the 1980s and 90s through the representation of woodfire leaders such as Ryoji Koie and Kato Tsubusa, the gallery is a leader in contemporary Japanese ceramic art. For this exhibition I have been presented the challenge by the gallery to create my own style of Iga ware. With months to prepare for exhibition I began prepping the chestnut fire wood while contemplating how to make the centuries old anagama tradition my own. I knew the gallery wanted me to remove my myself from the obvious tradition, to reinvent Iga, to add something new. But to do so in my individual way would require a sensitive balance as I desire to retain the essence of the ware in a natural uncontrived way. This element of making is perhaps the ultimate challenge to those working in the anagama today, how to add to any great tradition with out cheapening it with tacky novelty. As the days and sawdust flew bye I grew increasing lost in thought. In order to make Iga my own, I first must answer, what is Iga to me?

“In order to make Iga my own, I first must answer,

what is Iga to me?”

At university in 1997 I was researching Raku pottery for a course project when I stumbled upon a series of books titled Nippon Toji Zenshu, A Pageant of Japanese Ceramics. Flipping through volume after volume, gazing at photos of Shino, Tanba, Hagi, the great old kilns and their masterpieces felt right at my fingertips. When I opened the dusty volume on Iga, my life was radically transformed. I struggle to explain the realization, the emotional, spiritual, and intellectual awakening that occurred within me. I found what I had been looking for my whole life, art that connected with the core of my being. It was like falling in love and having your heart broken simultaneously. I had never encountered pottery that was this natural and rugged, dynamic yet sensitive, powerful but disciplined. Less than one year later I constructed my first small ramshackle anagama kiln from a pile of rubble salt kiln bricks and scrap clay and was stoking every month. Iga ware led me to wabi aesthetics, Zen Buddhism, and my new life in Japan. My clay and kiln research continues to this day and old Iga ware is a continual source of inspiration.

It is often best to define things initially through history. Iga ware dates back to the Kamakura period and possibly even back to the Heian. However before the Momoyama period of tea ware production, Iga pottery jars and mortars were very similar to that of nearby Shigaraki. It was under the patronage of medieval lord Tsutsui Sadatsugu and especially the guidance of Zen tea master Furuta Oribe that the highly distorted and stylized forms decorated with flowing natural ash glaze and phenomenal firing effects were created. Unfortunately there is little archeological evidence of the old Iga kilns and little research has been conducted. The primary source of recored is often tea ceremony diaries that indicate the earliest use of Iga water jar by Oribe in 1601. There are few surviving old Iga pots as only a few kilns existed and these kilns were only in operation for about 50 years. An interest in Iga tea ware has been included in the various art revival movements within Japan, most notably in the Show Era (1926-1989) with artist potters such as Kitaoji Rosanjin and Handeishi Kawakita creating Iga inspired work continuing to the later anagama kiln revival master Furutani Michio.

Today the community of Iga is an underwhelming suburbia, miles of chain restaurants and strip malls. The museum dedicated to the ancient masterworks that I visited in 2008 has been demolished and relocated without the museum space and museum quality pottery. Now famous for black Angus beef and a touristy Ninja museum, I frequent the city of Iga as it is the home of my favorite American style pizzeria, but I never stay long. Unlike Shigaraki or Bizen, a visitor would be unaware of the grand pottery tradition. The ware resides in the mountains, hidden from view. Now, just a few families bear the responsibility of maintaining the Iga ware legacy, called Tanimoto, and Atarashi. These families are the last remaining hope for the tradition as they own the few remaining sources of the carbon trapping feldspathic white Iga clay. In neighboring Shigaraki, where access to mountain clay veins is now almost impossible, potters create faux Iga, reserving the term for the pieces made with Shigaraki clay, but bearing the full force of the firebox of the anagama.

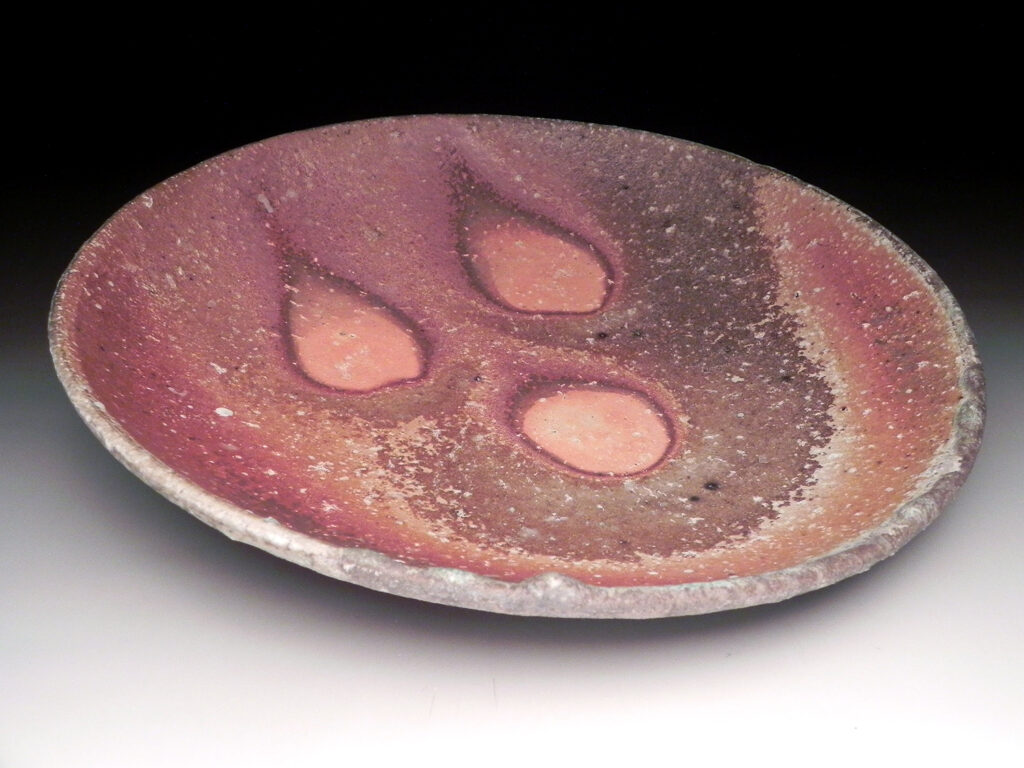

Typical formal pottery criticism is often an analysis on form and surface. In this regard Iga form stands alone in the field tea ware. With asymmetrical shapes that emphasize the plasticity of the clay, the pottery appears quickly manipulated and altered with nonchalance, directly faceted, and simply carved. The forms are often delineated with a drawn or engraved gestural marks composed on the freshly thrown wet clay the lines often appear as undulating grooves or hash marks that catch the flowing natural ash glaze. Perhaps the most distinguishing element of Iga form and my favorite is the mimi or ears. Often called lugs these applied decorative handles festoon the ware in dignified grace.

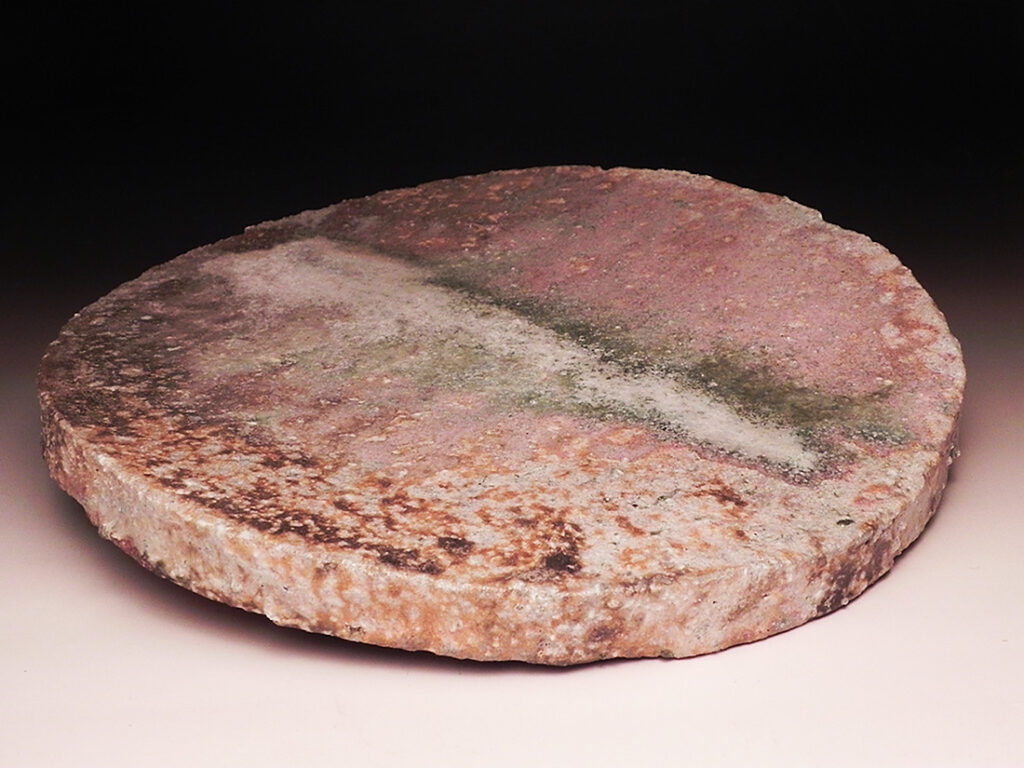

In anagama firing surfaces are often determined by our base materials such as wood and clay. Aware that I had no access to the treasured rare white Iga Clay similar to that used in the ancient masterworks, I set out to find what clays, if any, were available in the Iga area. After a few days of hunting and driving I was extremely excited about the discovery of one material I had not previously used, a refractory high iron clay dug by a professional clay digger in Mie Prefecture near Iga.

With limited time to test the clay in the anagama I decided it would be best to use this new red Iga clay in multiple ways to maximize the materials potential . I would make pottery with the red clay and mix clay body blends with my Kyoto and Shigaraki clays. I would use the clay itself as a type of flashing slip making a simple terra sigillata, and finally I would blend the clay into my Shino type glazes as a substitute for the kaolin and ball clay component in the recipe. With this new material I felt the work would be conceptually authentic through the inclusion of an Iga local material, that was largely unfamiliar, unexplored, and unused at large.

The iron bearing clay was difficult to work with however I believed it is an interesting and suitable material for the reduction cooling phase of my firing, aligning with my typical firing strategy that is based on heavy reduction to 1.200 ºC over two days, maintaining top temperatures for a third day of fast flame work (again in heavy reduction) and finally, a four hour reduction cool phase stoking down with unseasoned hardwood. This material would not provide the typical Iga wood fired surface landscapes but something new, different. Iga ware for me is about embracing the aesthetics of the natural wood kiln phenomenon, and I sought out to reference the surface intensity of old Iga in iron.

I do not know if formulating a body of pottery, let alone several anagama kiln firings for an entire exhibition based off a truck load of local wild clay is a good idea or if it even makes the work Iga, probably not. But after 15 years of potting in Japan I am growing less interested in defining my work in regionalist or traditional terms. I am interested in human expression in clay, and seeking new possibilities in clay and glaze discovery in partnership with my kiln. If I have created a new Iga it is by my own definition and considered standard. However the challenge of new materials, and the struggle to balance influence and appropriation remains.

More information about the exhibition at Gallery Utsuwakan Kyoto: www.g-utsuwakan.com