I met Sandy Lockwood at La Meridiana in Tuscany.

I’m new to ceramics, and after a few years working in a community studio in Alexandria, Virginia I thought it was time to get some more education. I enrolled in a three-month intensive course during the winter of 2023/4 at La Meridiana International School of Ceramics in Italy. My teacher for the course was Australian ceramicist Sandy Lockwood who is known in the ceramics world for wood firing, salt glazing, gorgeous tableware, and dramatic, earthy sculptures.

If you haven’t heard about La Meridiana, it’s a wonderful ceramics school established by the accomplished Italian ceramicist Pietro Maddalena. Amazing potters from around the world come to teach workshops there and students come from all over the world to study. I got to know students from Finland, Germany, Luxembourg, Italy, and England while I was there. Lucky for me, all the classes at La Meridiana are taught in English.

The school is set in a renovated 18th-century farmhouse not far from Siena and Florence, and one can enroll for short courses that run for a week or two or take a month-long or three-month-long intensive course as I did. It’s easy to study there because La Meridiana arranges housing for students in nearby guest houses and part of the cost of the course goes toward a delicious, healthy homecooked Italian lunch, served every weekday, with wine! If you’re traveling in the area, plan to stop in to check it out. Everyone there is very welcoming; email ahead and someone will be able to show you around.

During the three-month long intensive course, Sandy’s teaching focused on strengthening and building our throwing skills. One day a week, students met with Eve Carrobourg, a young French ceramicist, who taught us introductory glaze technology. This was truly invaluable; she demystified glaze chemistry and got us all thinking we could mix and design our own glazes.

In the final month of the session, Lockwood and Carrobourg together directed each of us to design our own personal project, and as an unexpected bonus Sandy offered to oversee a wood firing in one of La Meridiana’s three wood kilns. Most of us had worked mainly with electric kilns. At La Meridiana we all got our feet wet firing in gas kilns and cone ten reduction. What a revelation! But participating in a wood firing took us to another level. We all learned to wad. We took turns watching the temperature gauge and learned to stoke, which involved quickly tossing the wood onto the fire without knocking down the pots placed at the entrance of the firebox.

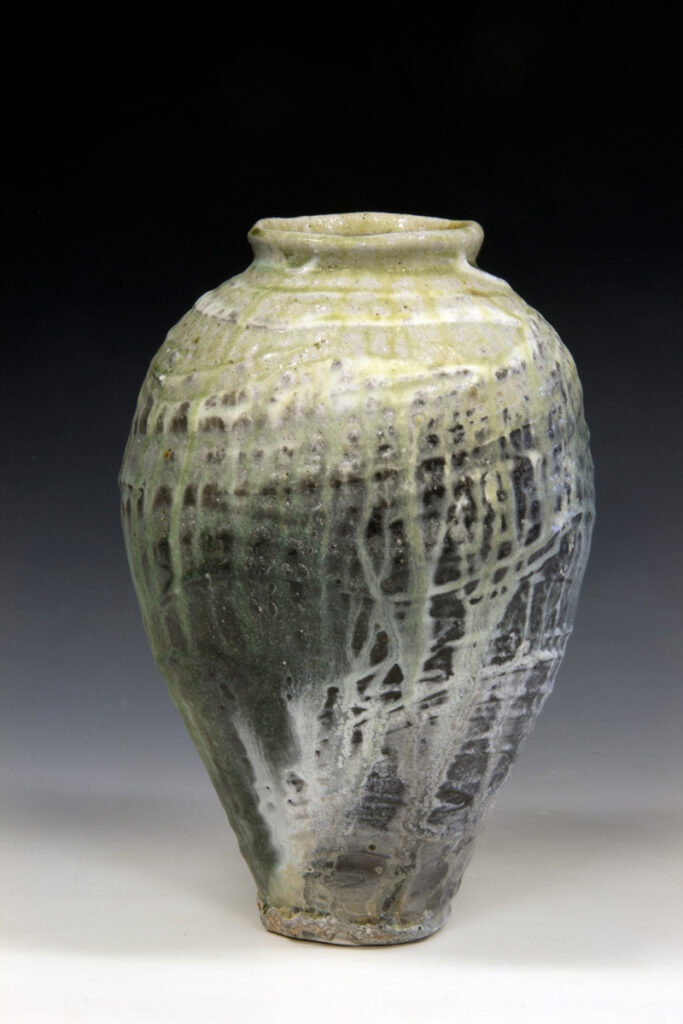

It was a successful firing, and we all ended up with a lot of good-looking pots. To my delight, I got a fantastic piece from this my first wood firing: a large amphora decorated with poured chun, oribe and slip. My tall pot got to stand near the top of the arch and was beautifully bathed in flashing marks that complemented the liquidity of my glaze application.

Visiting Sandy Lockwood’s Balmoral Pottery in Australia.

Some months after returning to the states, I managed to wrangle a stay with Sandy and her husband Colin Todd at their Balmoral Pottery in New South Wales, Australia. Their place is somewhat remote. As they say, “it’s in the bush.”

Working alongside her in the studio, I came to see that, like many wood fire ceramicists, Sandy sees her wood kiln as more than just a tool; she sees it as a true collaborator. She writes about this in her 2018 thesis (University of Wollongong), pointing to historic metaphors used to liken wood kilns to living breathing creatures. She watches for signs from the kiln such as sound, smell, atmosphere, and color in the chamber as she fires. And Sandy is always working on improving her communication with these collaborators. Careful observation of how pots fire in various locations inside the kiln is one way that she does this. Skillfully observing the pots as they come out of the kiln, Sandy writes little notes about each of the pieces she is developing, which clay, slip, and glaze she used and where it was in the kiln —and she drops these small notes inside to ponder in more detail later in the studio. In the end, when the pots are just about ready to leave the studio to meet the public, she sits down with one of her studio journals and records her findings. Sandy has a whole library of journals, and she can put her hands on notes taken from past firings in a matter of minutes.

I find Sandy’s way of thinking about the kiln environment thought-provoking. She likens the transformation of clay to metamorphosis resulting from an extreme weathering event orgeological disturbance. Through her I’ve begun to see the interior of the wood kiln as a dramatic wind-swept environment where weathering processes are sped up, where earth is transformed by the forces of air and heat. One could say that Sandy’s poetic imagination thinks in geological time, imagining magma melts and water and wind erosion over millennia.

Of course, clay is the foundation of Sandy’s color palette. But instead of sticking to a few tried-and-true clays bodies, her insatiable curiosity keeps her experimenting with new ones, adjusting the raw material components of the clay she uses and trying different sources. She varies the fluxing agents, and adds materials such as found clay, gravel and stone. I heard her talking about using ant hill material in one body. She also carefully observes clay tests in different spots in the kiln and compares the results of different clay recipes treated with the same glaze. These clay recipe comparison boards dot her studio. In this way, she keeps building her rich earthy color palette and adding more varied surface textures. It’s no surprise that Sandy is drawn to the beauty of paleolithic and neolithic pottery and stone artifacts, as these handmade objects generally show evidence of thousands of years of wear and tear. She likens the effects of time, wind, and rain on neolithic standing stones to the way that the weather sculpts the land, and the organically rounded, irregular silhouette of eroded stone or ceramic artifacts is the same visual vocabulary she brings to her sculptural work and her tableware and jars.

It was a treat to see Sandy’s sculpture on view in her small gallery showroom and hanging on the exterior walls of her studio and exposed to the elements. Although these pieces are not large, they echo the shapes of a long-buried axe head or heavily worn ancient grinding querns. For me, Sandy’s sculptures communicate a strong sense of weight and density but also fragility.

As I used her plates and mugs at meals, I never lost my sense of wonder at the beauty of Sandy’s tableware, and I couldn’t help but recognize the sculptural quality of her plates and bowls. Sandy’s throwing philosophy emphasizes the evidence of the hand. Watching her throw, I was struck by how the pieces that emerged from the matrix of her fingers unfolded like a series of gentle waves. Instead of a consciously designed pattern, Sandy’s throw lines look like the pattern left in sand by ocean waves, rich with metaphorical associations. Her plates look like snow blown across a barren landscape or the slightly eccentric orbital pattern of celestial bodies. And the surface of her salt glazed mugs sometimes reminds me of sugar glaze or water in the process of turning to ice. The aesthetic appeal of Sandy’s tableware isn’t only visual; it has a slight heft that gives it a satisfying tactile immediacy. When using it, one’s body feels its substance and solidity.

Reading back over this, I see that I‘ve written a thank you letter to Sandy and Colin. Sandy was an amazingly generous teacher at La Meridiana, who took the time to cultivate her students’ personal artistic growth. And I can’t thank her and Colin enough for inviting me into the circle of their family in a far-off land where kangaroos eat grass in the yard and brilliantly colored parakeets come close begging for sunflower seeds.

Patricia Briggs is an art historian and ceramic artist based in Alexandria Virginia.

Sandy Lockwood: www.sandylockwood.com.au

Patricia Briggs: @patriciabriggsceramics